The Man from London

A Londoni férfi, Hungary/France/Germany, 2007, 139 mins, black and white

(Another one from the archives, originally published in the January 2009 issue of Sight & Sound as a two-page lead review and posted here to mark the death of its director Béla Tarr, announced yesterday.)

Director: Béla Tarr • Head of Production: Gábor Téni, Paul Saadoun, Miriam Zachar, Joachim von Vietinghoff, Christoph Hahnheiser, for T.T. Filmműhely, 13 Production, Cinema Soleil, Von Vietinghoff Filmproduktion, Black Forest Films • Screenplay: László Krasznahorkai, Béla Tarr, based on the novel ‘L’homme de Londres’ by Georges Simenon • Cinematography: Fred Kelemen • Editor/Co-director: Ágnes Hranitzky • Production Designers: László Rajk, Ágnes Hranitzky, Jean-Pascal Chalard • Costumes: János Breckl • Sound: György Kovács

Cast: Miroslav Krobot (Maloin, nightwatchman), Tilda Swinton (Camélia, Maloin’s wife), Erika Bók (Henriette), János Derszi (Brown), Ági Szirtes (Brown’s wife), István Lénárt (London police inspector), Gyula Pauer (publican), Mihály Kormos (Brown’s assistant), Kati Lázár (Henriette’s boss), Éva Almássy Albert (pub whore), Ági Kamondy, László FeLugossy, Philippe Guerrini, Jacques Pilippi, Alfréd Járai

The extinction of the aesthetically and intellectually rigorous European art film has been predicted for so long (in the early 1980s, a Sight & Sound columnist called for the creation of a Society for the Protection of the Art Movie) that the mere fact of Hungarian auteur Béla Tarr continuing to direct films without making the smallest concession to popular fashion is a cause for celebration.

Tarr’s mature style was first fully unveiled in his fifth feature, Damnation (Kárhozat, 1988) which combined harshly-lit black-and-white cinematography, lugubrious characterisation and pacing (shots lasting several minutes longer than narratively necessary), and the ‘Tarr trudge’ charting every step of a person’s lengthy, silent walk. Damnation was followed by his masterpiece Sátántangó (1994), whose seven-hour-plus running time ensured minimal theatrical distribution. Werckmeister Harmonies (Werckmeister harmóniák, 2000) was a more conventional length, but in all other respects this allegory saw Tarr reaching for a cosmic view of a fundamentally disordered universe.

The Man from London (A Londoni férfi) was finally completed in 2007 after numerous hitches, including the suicide of original producer Humbert Balsan. Disconcertingly, the credits suggest a conscious attempt by Tarr to broaden his audience. László Krasznahorkai remains his co-screenwriter, but the source material is a slim 1933 novel by popular Belgian writer Georges Simenon (filmed as L’Homme de Londres by Henri Decoin in 1943 and as Temptation Harbour by Lance Comfort in 1947). The cast includes Tilda Swinton, the setting is coastal France and the synopsis suggests a murder mystery, with all the generic pleasures that implies. In fact, Tarr has expunged every element that doesn’t fit his worldview. The result is as typically uncompromising as his other work.

Tarr has created some of the most striking opening sequences in modern cinema (cows roaming a deserted hamlet in Sátántangó, drunken barflies becoming a working model of the solar system in Werckmeister Harmonies) and The Man from London is no exception. A foghorn that seems to sound across the harbour where much of the action takes place is actually the first note of Mihály Vig’s score, its rising theme accompanying depth markings on the hull of a ferry, as if defining its musical intervals. The eye is also occasionally deceived, as a single porthole echoes the eye of Werckmeister’s whale, the shadows passing over the ferry’s hull and the upward camera movement suggesting a gigantic sea creature emerging from the depths. We then hear a transaction taking place between two men, but can’t see their faces. The details of the deal are equally skimpy; we find out only much later that the men’s names are Brown and Teddy.

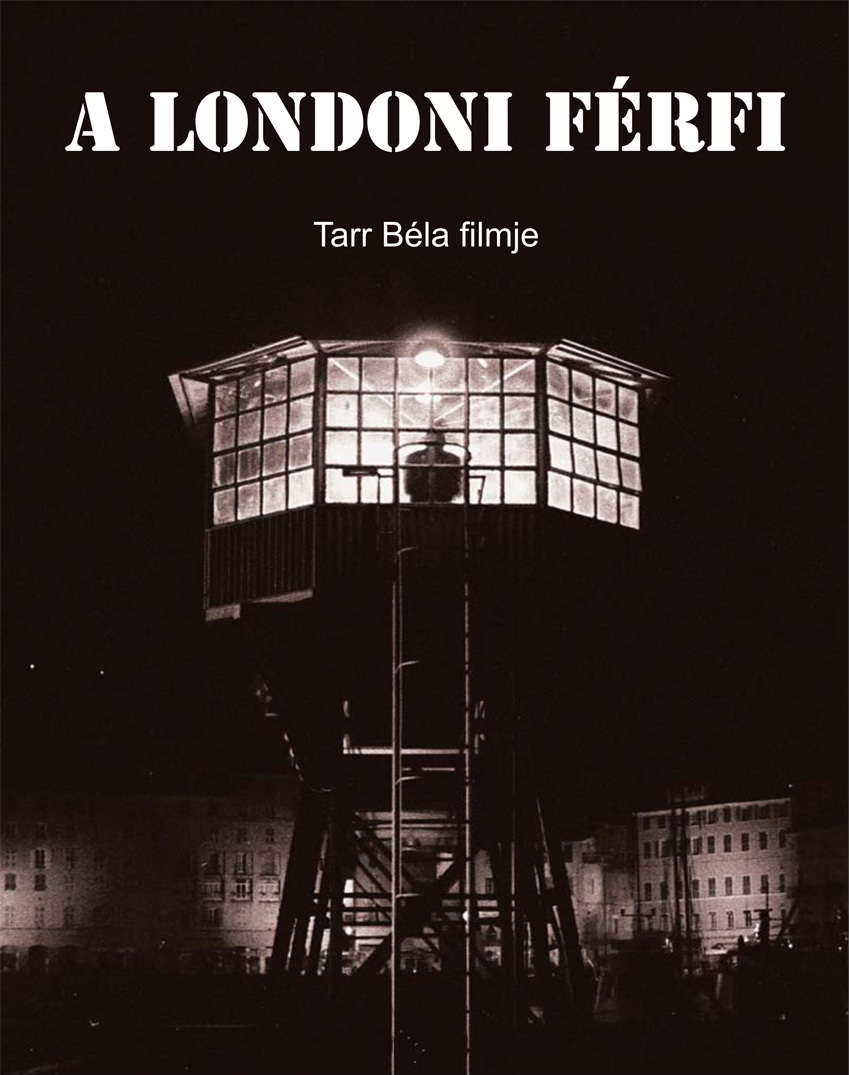

Everything is seen from the restricted viewpoint of nightwatchman Maloin (Miroslav Krobot) who sits in an elevated glass cage with a panoramic view of the harbour. Shadows add a consistent visual rhythm, generated by out-of-focus window-frames passing the camera. The distance makes it hard to interpret what’s happening: Maloin can only see what appears to be a case of import fraud (a suitcase is tossed over the far side of the ferry, unseen by the waiting customs officials) followed by a quayside struggle that ends with Teddy falling into the sea and Brown hiding out in the local café. Maloin retrieves the suitcase and discovers that it’s full of damp British banknotes, which he dries on the signalbox’s woodfired heater. Tarr is exceptionally attuned throughout to the physicality of both the surrounding space and the objects within it.

This nocturnal sequence, comprising five shots and lasting nearly a fifth of the running time, seems to set up The Man from London as the kind of mystery-cum-robbery thriller alluded to by the credits, but neither Maloin nor Tarr have much interest in the ensuing investigation. This is underscored by the willingness of the police inspector Morrison (István Lénárt), to offer financial inducements to clear things up quickly. We also never find out what happened between Maloin and Brown in what would be a climactic confrontation in a more conventional film.

The film instead focuses on Maloin and the crushing pressure that the money applies to his conscience. His social circle revolves around the gloomy café proprietor with whom he plays silent games of chess, his semi-estranged wife Camélia (Swinton) and his daughter Henriette (Erika Bók, the cat-murdering waif in Sátántangó). Maloin won’t discuss his changed circumstances, and his attempts at lifting Henriette out of the misery to which she is resigned (like most Tarr characters) involve him theatrically dragging her away from her job as a delicatessen assistant. In the film’s only overtly comic scene he kits out Henriette in a fur stole; the garrulous fur salesmen seem to have escaped from The Fast Show, so out of step are they with the prevailing mood. But without being able to explain their new wealth, his relationship with Camélia deteriorates further.

Tarr adapted Macbeth for Hungarian television in 1982, so he will certainly know Duncan’s maxim “There’s no art to find the mind’s construction in the face.” However, he seems determined to disprove this in The Man from London, subjecting most characters to a typically lengthy camera-stare. Strangely, these shots never become boring, largely due to the chance they offer of examining an extraordinary collection of facesin perfectly-lit close-up: Maloin’s world-weary jowls, Morrison’s rumpled skull-head and Henriette’s unnervingly inscrutable smile.

At festivals, the film generally played in Hungarian, though Tarr has since reworked the soundtrack into French and English. Both dubs include less-than-felicitous lip-sync (Krobot and Swinton in both versions). The Hungarian feels more authentic, partly for linguistic continuity with Tarr’s previous work, but mostly because Lénárt has the lion’s share of the onscreen monologues. However, the Anglo-French version makes more situational sense and renders Maloin deaf as well as blind to events. Although present during many crucial conversations, it’s unlikely he understands them, and the French précis he’s given by the café proprietor and Morrison is so selective as to be useless. The English dub also adds a note of class conflict, with Morrison’s patrician tones (Edward Fox) set against Brown’s glottal stops.

There are fewer ‘Tarr trudges’ than usual, though a suggestive shot sees Maloin walking along the quayside framed against a church in the background, the almost imperceptible camera movement implying that it’s never getting any closer; this religious overtone intimating that everything that happens to him derives solely from his own actions, with no external assistance. Despite Maloin’s God’s-eye view of the harbour, and control over great machines, he remains trapped in his own self-circumscribed world, unable to cope with any far-reaching changes.

Stretches of The Man from London may hint that Tarr is caught in a similar creative impasse (the film is closer to the territory of Damnation than its immediate predecessors), but the peculiar pleasures of his cinema are still to the fore. Chief among them is the silvery black-and-white cinematography by fellow director (and former Tarr student) Fred Kelemen, whose virtuosity in lighting, movement, and composition is breathtaking, recalling the great noir specialist John Alton while remaining absolutely true to Tarr’s vision.