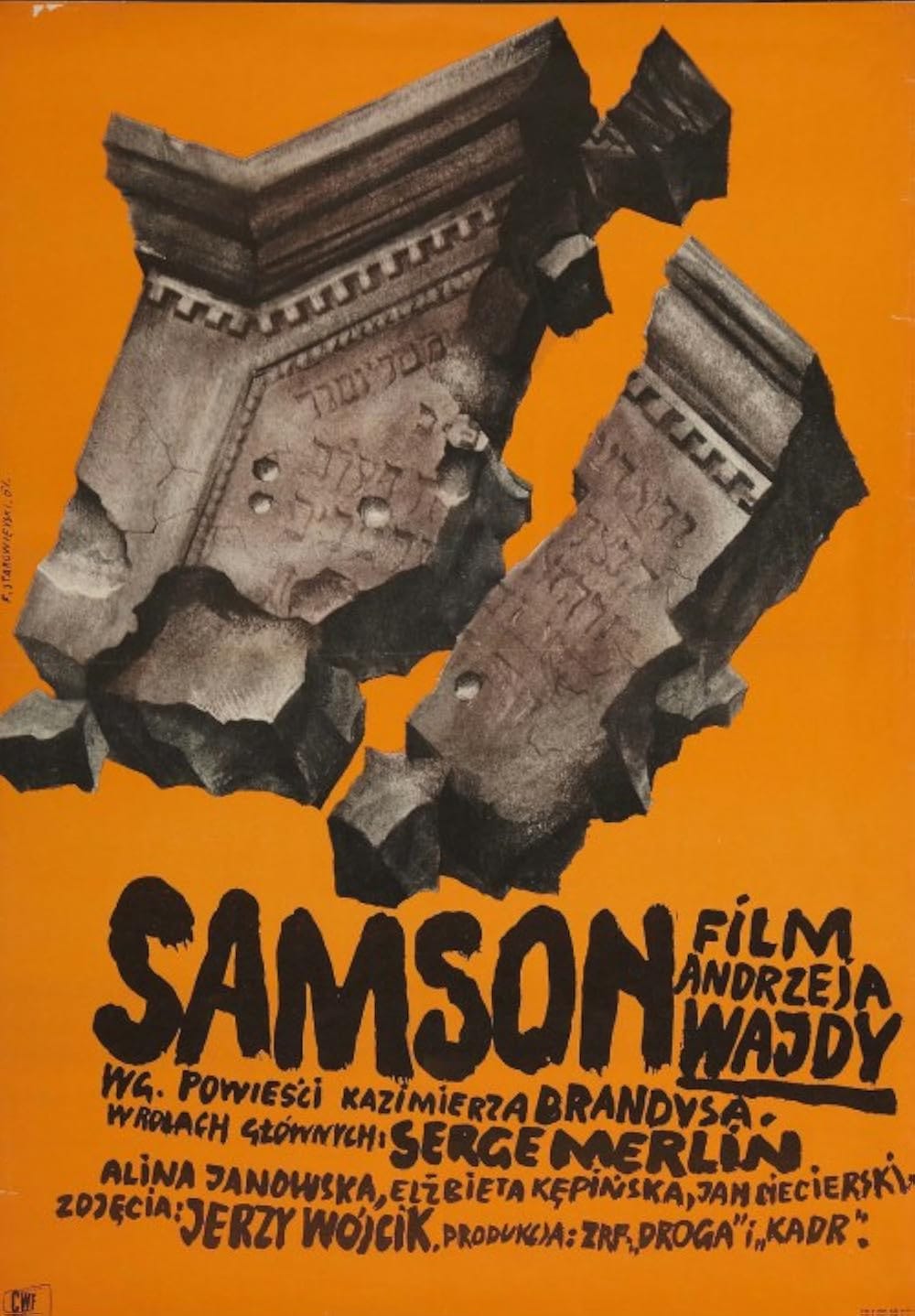

Samson

Poland, 1961, 117 mins, black and white

Director: Andrzej Wajda • Head of Production: Stanisław Daniel, for Zespół Filmowy Droga, Zespół Filmowy Kadr • Screenplay: Kazimierz Brandys, Andrzej Wajda • Cinematography: Jerzy Wójcik • Editing: Janina Niedźwiecka • Production Designer: Leszek Wajda • Costumes: Jan Banucha, Wiesława Chojkowska • Music: Tadeusz Baird • Sound: Józef Bartczak

Cast: Serge Merlin (Jakub Gold), Alina Janowska (Lucyna), Elżbieta Kępińska (Kasia, Malina’s niece), Jan Ciecierski (Józef Malina), Tadeusz Bartosik (“Professor” Pankrat), Władysław Kowalski (Fiałka), Irena Netto (Jakub’s mother), Beata Tyszkiewicz (Stasia), Jan Ibel (Genio), Bogumił Antczak (prisoner serving dinner), Wiesława Chojkowska (Wiśka), Edmund Fetting (Zygmunt, guest at Lucyna’s party), Roland Głowacki (guest at Lucyna’s party), Andrzej Herder (German in the printing house), Zygmunt Hübner (Gestapo officer), Zofia Jamry (Genio), Stanisław Jaśkiewicz (professor entering the lecture), Zbigniew Józefowicz (guest at Lucyna’s party), Edward Kowalczyk (policeman), Zygmunt Listkiewicz, Jerzy Łapiński (carol singer), Zdzisław Maklakiewicz (ONR activist throwing brick), Zygmunt Malawski (printer), Roman Polański (partner of the woman blackmailing Malina)

Having made four successive films with a WWII (or immediately after) setting, Andrzej Wajda briefly changed direction with Innocent Sorcerers (Niewinni czarodzieje, 1960), set entirely in the then present day. However, his sixth feature Samson saw him return to 1930s/40s Poland again—albeit for the last time for nearly a decade.

But Samson differs from its predecessors in quite a few respects. Firstly, it’s the first of several Sixties films to be shot in anamorphic widescreen, necessitating a different approach to framing and cutting. (Wajda later admitted that he never got on with full-on widescreen, and most of his films from the late Sixties onwards would revert either to standard European widescreen or even the squarish Academy frame, by then largely obsolete in the so-called West, that he used for most of his 1950s films.) Secondly, it’s laser-focused on a single protagonist, something that wasn’t true of his previous WWII films—even Ashes and Diamonds (Popiół i diament, 1958), for all the power of Zbigniew Cybulski’s overwhelming performance, has several subplots that don’t involve his character. And thirdly, that protagonist is Jewish.

Not that he’d completely ignored the plight of Jews in Poland: A Generation (Pokolenie, 1955) had a minor Jewish character, Abram (Zygmunt Hobot) who was fatally caught up in the 1943 liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto, and one of Wajda’s first strongly politicised images was the one in that film where Poles enjoy themselves at a fairground while the ghetto visibly burns in the background. But here, the protagonist Jakub Gold is himself Jewish, something he’d never been especially bothered about until it becomes a literal matter of life or death.

Tadeusz Baird’s doom-soaked orchestral score sets the despairing tone from the opening credits, after which we see Jakub, then a university student in the 1930s, spotting some kind of student protest, and instinctively wanting to join it—not because he’s keen to champion their cause (he doesn’t initially know what it is) but just so that he can fit in, and for much of the rest he’ll similarly try to fit in. But if the aim of joining the crowd is to avoid being noticed, he disastrously miscalculates here, as the demonstration turns out to be an explicitly anti-Semitic one, and when his ethnicity is identified and he’s duly roughed up, he kills one of his tormentors (an ultra-brief acting cameo from a twenty-year-old Andrzej Żuławski) in self-defence, earning him a ten-year prison sentence.

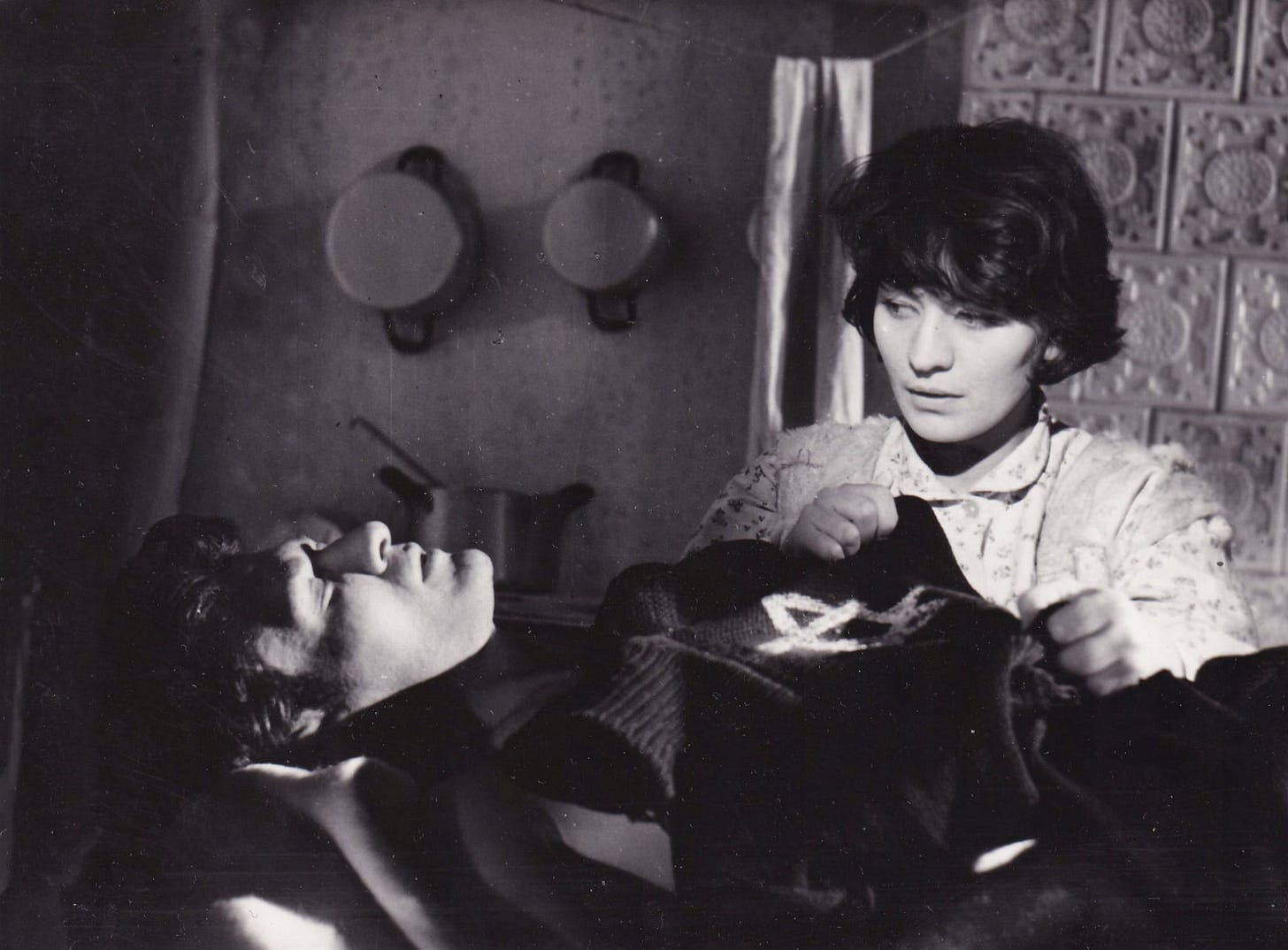

In prison, he’s deliberately scalded with hot soup as a punishment for failing to join a prisoners’ riot, but he presumably knew that he’d be likely to be more severely punished because of who he is. But what he also discovers in prison is genuine camaraderie, most notably from the former accountant Józef Malina (Jan Ciecierski), jailed for embezzling funds in order to cure his only son of a rare cancer, one of many events in the film that triggers an ethical debate about whether one should scrupulously obey the law if the law itself seems to be actively working against your situation.

The first half sees Wajda on superb form, with one powerful set-piece after another, and Jakub very much coming across as a successor to Tadeusz Janczar’s character Jasio Krone in A Generation, in that he’s instinctively wary of pretty much everything, even more understandably than Jasio was. Along with his fellow Jews, he passively watches himself being walled into the Warsaw ghetto (where he works as a gravedigger and helps retrieve corpses from the street, including that of one of the people most dear to him), and only escapes when he realises that the alternative is being shot; later, he’ll try to get back in after discovering that the outside is no better, at least for the likes of him. One of the most sickeningly powerful lines in the film comes when he comments that the compulsory Star of David on the backs of Jewish people’s coats gives Nazi gunmen a target to aim for, but they’re also the only people he can truly trust—outside the ghetto he’s constantly at risk of betrayal by understandably terrified people who don’t themselves want to be shot for harbouring a Jew.

It’s little wonder that Jakub increasingly tries to disappear into his own little world, replacing his prison cell and the ghetto with a basement from which he prefers not to emerge, just sitting rocking in a chair and being kept in a state of blissful ignorance to the point that he doesn’t even know that one of his hosts has recently died. But while this makes psychological sense, in the context of a Holocaust drama it feels like a cop-out, as though Wajda went an impressively long way down a particular road only to turn back just before reaching the inevitable destination, and the final scenes (where the overarching Old Testament-sourced Samson metaphor is spread with the proverbial trowel) similarly feel as though Jakub’s director is also trying to block out the horrors by simply ignoring them.

That said, with a film like Samson it’s always worth bearing in mind the historical context, because in 1961 Holocaust films, or at least fictional dramatic features, were still as rare as the proverbial hen’s teeth; there’d been a couple of near-simultaneous Polish and Czechoslovak efforts in 1948 (Wanda Jakubowska’s The Last Stop/Ostatni etap and Alfréd Radok’s Distant Journey/Daleka cesta), as well as Aleksander Ford’s Border Street/Ulica Graniczna from the same year, about the uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto, but throughout the subject fiction feature filmmakers tended to either avoid the subject altogether or treat it obliquely until Gillo Pontecorvo’s Kapò in 1959 took us into the death camps.

And although the number of Holocaust-themed feature films would increase in the 1960s (the first important American one being Sidney Lumet’s The Pawnbroker in 1964), Samson is still one of the earlier ones, and one of the first by an unimpeachably major director. (Andrzej Munk would shoot his own Holocaust drama Passenger/Pasażerka very soon afterwards, but production was abandoned when Munk was killed in a car accident in 1961, and the film ultimately released incomplete in 1963.)

This being the case, and also recalling that the Holocaust happened less than two decades before Samsonwas made, it’s easy to understand Wajda’s hesitancy in grasping this particular nettle—like Jakub Gold himself, he seems understandably unsure about how best to dramatise it, and so he increasingly falls back on symbolism in lieu of psychological probing, some of it decidedly clunky, e.g., the scene of Lucyna (Alina Janowska) cutting her hair, prolonged just in case we don’t immediately grasp its significance in the context of a film called Samson. In fact, the whole Jakub-as-Samson metaphor is somewhat strained, although it originated in Kazimierz Brandys’ source novel. Ironically, nearly three decades later, Wajda would himself become the inspiration for another filmmaker who was similarly very hesitant about making his own Holocaust film, when the far more confident Korczak (1990) became not just a major influence on Schindler’s List (1993) but the film that persuaded Steven Spielberg that his film was viable in the first place.

Jakub is played by the French stage actor Serge Merlin, making what I believe was his big-screen debut; decades later, he’d become most famous for playing the reclusive neighbour in Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s Amélie (Le Fabuleux Destin d’Amélie Poulain, 2001), and in between he appeared in two more Wajda films, Danton (1982) and A Love in Germany (Eine Liebe in Deutschland, 1983). Unsurprisingly, and somewhat obviously, he’s been dubbed into Polish, which has the effect of further “othering” him—an effect that may well have been intentional from the moment of casting. (He’s dubbed by Władysław Kowalski, who also plays the minor supporting role of Fiałka onscreen, although I don’t recall any prolonged conversations between the two characters.)

In previous pieces, I’ve mentioned how future directors Roman Polański, Kazimierz Kutz and Jerzy Skolimowski started their careers as Wajda protégés, and Samson credits two more: the still seriously underrated Barbara Sass, then going under her married name of Barbara Zdort, and Andrzej Żuławski, who would remain Wajda’s on-off assistant for much of the rest of the decade, and Wajda would later act as midwife to his first two features, the second of which, The Devil (Diabeł, 1972) was produced by Wajda’s own X Film Unit. There’s also a wittily-cast Polański cameo where he plays the dapper, neatly-moustached husband of a fanatical Jew hunter with blackmail on her mind—Polański of course having famously been on the receiving end of such hunts while growing up in the Kraków ghetto. And while this is unlikely to have been a deliberate foreshadowing of the eponymous 1981 film, there’s a retrospectively nifty line about the Communist prisoner Pankrat (Tadeusz Bartosik) being “a man of iron—but I’m not sure people should be made of iron”.