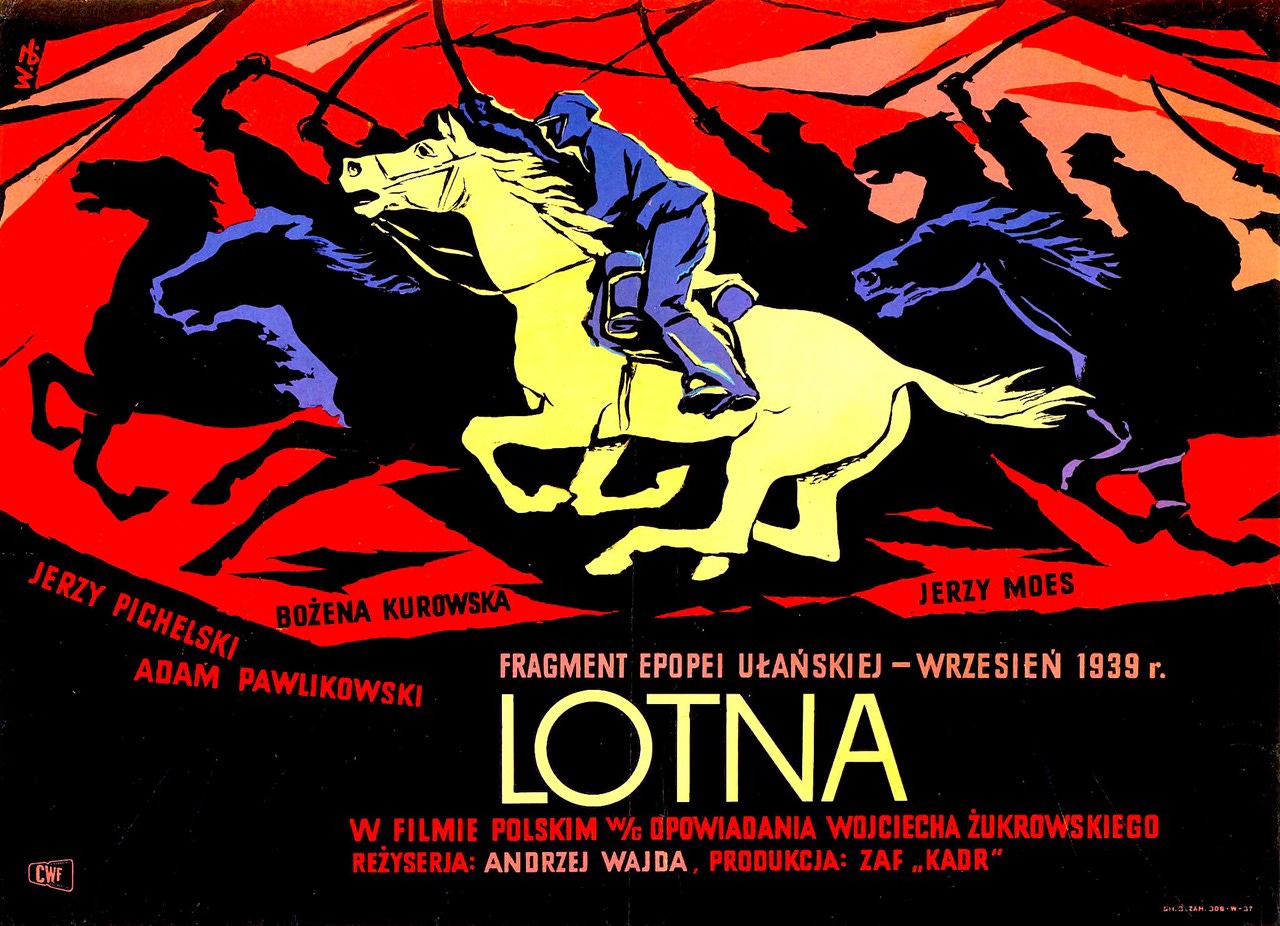

Lotna

Poland, 1959, 85 mins, colour

Director: Andrzej Wajda • Head of Production: Stanisław Adler, for Zespół Filmowy Kadr • Screenplay: Wojciech Żukrowski, Andrzej Wajda, based on the novel by Wojciech Żukrowski • Cinematography: Jerzy Lipman • Editing: Janina Niedźwiecka • Production Designer: Roman Wołyniec • Costumes: Lidia Gryś, Jan Banucha • Music: Tadeusz Baird • Sound: Leszek Wronko

Cast: Jerzy Pichelski (Cavalry Captain Chodakiewicz), Adam Pawlikowski (Lieutenant Witold Wodnicki), Jerzy Moes (Cadet Officer Jerzy Grabowski), Mieczysław Łoza (Second Sergeant Latoś), Bożena Kurowska (Ewa), Bronisław Dardziński (moonshine maker), Adam Dzieszyński (uhlan), Wiesław Golas (soldier catching chickens), Henryk Hunko (uhlan), Tadeusz Kosudarski (uhlan), Artur Młodnicki (colonel), Irena Malkiewicz (countess), Karol Rómmel (pastor), Tadeusz Somogi (uhlan), Bolesław Woźniak (uhlan), Marian Wiśniowski (uhlan)

I’ll be writing about the longstanding friendship between Andrzej Wajda and Steven Spielberg in more detail in a few weeks—probably in tandem with Korczak (1990)—but when thinking about Lotna I couldn’t help but be struck by parallels between their careers at a similar stage (i.e. a fourth theatrical feature in their early thirties) in which both attempted to follow up two huge box-office hits that were also widely acclaimed as artistic masterpieces with ambitious films about the widespread confusion that hit their respective countries after they came under surprise attack in events that sucked them into WWII.

I don’t want to overstress comparisons with 1941 (1979), because they’re tonally very different—1941 is a comedy (and, for all the negative press that it’s picked up, often a genuinely funny one), while Lotna is granite-facedly serious—but they were both notorious critical and commercial flops that happened to directors who’d known nothing but dazzling success up to then. Furthermore, they were widely assumed to be flops specifically because both Wajda and Spielberg had overreached themselves, something that both men admitted to later. Indeed, Wajda said that if he had the chance to remake any of his films, he’d pick Lotna, as he was fully aware from a very early stage of production that it wasn’t turning out the way he was hoping.

One problem was that it was by far his most personal film to date. Whereas Kanal had at least touched on Wajda’s own activity as a teenage Home Army courier, Lotna is about Polish cavalry officers at the time of the Nazi invasion of September 1939 (the parallel Soviet invasion is, of course, not mentioned)—and Wajda’s father Jakub was himself a cavalry officer, who a few months later would be one of the victims of the massacre of Poland’s military and intellectual élite in the Katyń Forest near Smolensk in the Soviet Union, something else that his son was unable to allude to.

Lotna started life as a short story by Wojciech Żukrowski, to which Wajda was initially attracted because of its central conceit: that the central character was a horse rather than a human being, and its subsequent death represents the death of the Polish uhlan, or light cavalry, and with it the death of a Polish tradition that dated back to the Napoleonic era (which he would subsequently dramatise in his 1965 epic The Ashes/Popioły).

He’d already alluded to the uhlan tradition in passing in Kanal via an almost throwaway line in which a soldier in the 1944 Warsaw Uprising is called an “uhlan” rather than a “żolnierz”, and in discussing Lotna in interviews Wajda would reminisce about growing up around the military training grounds where his father worked, where he’d see the fresh-faced recruits learning how to wield their sabres at full gallop (and they were severely punished if they inadvertently injured their horses in the process), attacking human-shaped dummies with their lances, and so on. It must have been thrilling for the young Andrzej to watch a great Polish tradition being maintained before his very eyes—indeed, who’s to say that Wajda might not ultimately have followed in his father’s footsteps under different circumstances?

But the problem with the film was that although it was unambiguously celebratory about the history and traditions of the uhlans, it also played into one of the most insidiously pervasive of all WWII myths in a way that many Poles interpreted as a wounding personal insult. The film’s most spectacular set-piece showed uhlans mounting a full-blown cavalry charge against a German invasion that included tanks—something militarily ridiculous, because no mere horse and sabre, however deftly mustered, is going to be a match for a tank, and no sane officer is going to give the order for such an obviously suicidal mission.

Wajda clearly saw it as a great Romantic-tragic image, his inspiration fired up by the popular saying “with swords against tanks” (“z szablami na czołgi”)—an English equivalent might be “to bring a knife to a gunfight”—but the problem was that such an encounter never actually happened, or at least not in the way that Wajda so vividly depicted it. The real-life inspiration happened on 1st September 1939, the day of the German invasion of Poland, in which the 18th Pomeranian Uhlan Regiment executed a successful surprise charge on a battalion of German infantry in the village of Krojanty, but when armoured cars emerged from the nearby Tuchola Forest they were forced to retreat. Although it was a pretty even-handed encounter until the armoured cars arrived, German and Italian propagandists quickly turned it into a powerfully anti-Polish narrative in which heroic but backward Polish uhlans were sent on suicide missions against German tanks by their callous incompetent superiors.

And although historians have debunked this myth ever since, demonstrating that the Polish cavalry of 1939 was in fact a modern mobile infantry force fully equivalent to their German counterparts in terms of equipment and training, with horses very rarely used in actual combat, it remains a potent and powerful image that still pops up even this side of the millennium changeover. A 2009 article in The Guardian uncritically repeated the myth, and had to run a correction (subsequently added to the start of the original article), and they later printed an article exploring the myth directly. The latter didn’t mention Wajda’s film, but because it had never received British distribution in any form that’s hardly surprising. Indeed, the film is rare enough in Poland: it was omitted from a Wajda-supervised 36-DVD box set that included much of the rest of his output, it’s not available on Blu-ray, and the only DVD edition that I’m aware of came out in 2005. It’s still available from some online retailers, but at a price several times more than I paid for it, suggesting that it’s long out of print.

Anyway, the problem was that Wajda—by his own rueful admission—failed to take into account the fact that the mere phrase “with swords against tanks” is nowhere near as potent or loaded as its large-scale visualisation, and that until his film came along, the only people who’d attempted to visualise it had been actual Nazi propagandists. And this scene was not in Żukrowski’s story; it was added by Wajda, who was so fixated on the central image of the horse as Romantic metaphor that he didn’t stop to think about precisely what he was dramatising and what effect it might have on the viewer.

It didn’t help that this was comfortably his toughest production in terms of logistics. All of his previous features had been ambitious to some extent, especially Kanal, but with Lotna numerous serious mistakes were made at a very early stage of production. For starters, professional actors who were also plausible horsemen were so thin on the ground as to be all but nonexistent. Top-billed Jerzy Pichelski had learned how to ride in his teens, and had even fought in the 1920 Polish-Bolshevik War (another taboo topic at the time, since the Poles won), but this was decades ago and he was badly out of practice. The other actors had to be trained outright, and there was a shortage of appropriately qualified trainers.

And there were problems with the horse herself. Colonel Karol Rómmel, the film’s cavalry consultant, initially found what he and Wajda thought was the perfect horse, a grey Arab mare, just as Żukrowski had specified. But she was killed only a few days into shooting after being accidentally impaled on a lance, something that Wajda not unreasonably interpreted as a bad omen. The horse was replaced, but by one that inevitably looked slightly different, which nonetheless had to be intercut with extant footage that was impossible to reshoot. Incidentally, Rómmel plays a brief cameo as a priest whose horsemanship puts everyone else’s in the film to shame; this is one of the few moments where the film achieves the kind of uncomplicated celebration of Polish tradition that Wajda had been aiming for.

To add to the complications, Lotna was Wajda’s first colour film, and the East German Orwo stock turned out to be so insensitive that cinematographer Jerzy Lipman blew up an electricity substation while trying to light an interior scene—and in the end Wajda and Lipman shot all the night scenes on black-and-white stock which they then tinted sepia on the final prints. Exteriors were shot in October 1958, which Wajda only realised was a scheduling error when it was too late; the golden autumnal hues might not have been a problem in a black and white film, but they were seriously jarring in a colour film whose events were famously set at the start of September.

The tragedy of Lotna is that you can still just about sense the epic that Wajda clearly intended to make, continuing to fuse an essentially Romantic conception of his doomed heroes with striking and sometimes bizarre images that nudge Surrealism (I’m thinking of the stuffed eagle—the emblem of Poland—bursting into flames), as indeed does the film’s overarching concept, that of 19th-century uhlans trying to maintaining their old traditions in a 20th-century environment. At this stage in Wajda’s career, Luis Buñuel was one of his favourite directors (in his memoirs, Buñuel would return the compliment), and by the time he made Lotna he’d caught up with much of the major work (at least to date; Buñuel still had plenty of masterpieces ahead of him). But Buñuel emphatically did not have a Romantic worldview, and images that seemed wholly logical in his films seemed weirdly incongruous and jarring in Lotna—not least to a Polish audience that wasn’t especially versed in Surrealism in the first place.

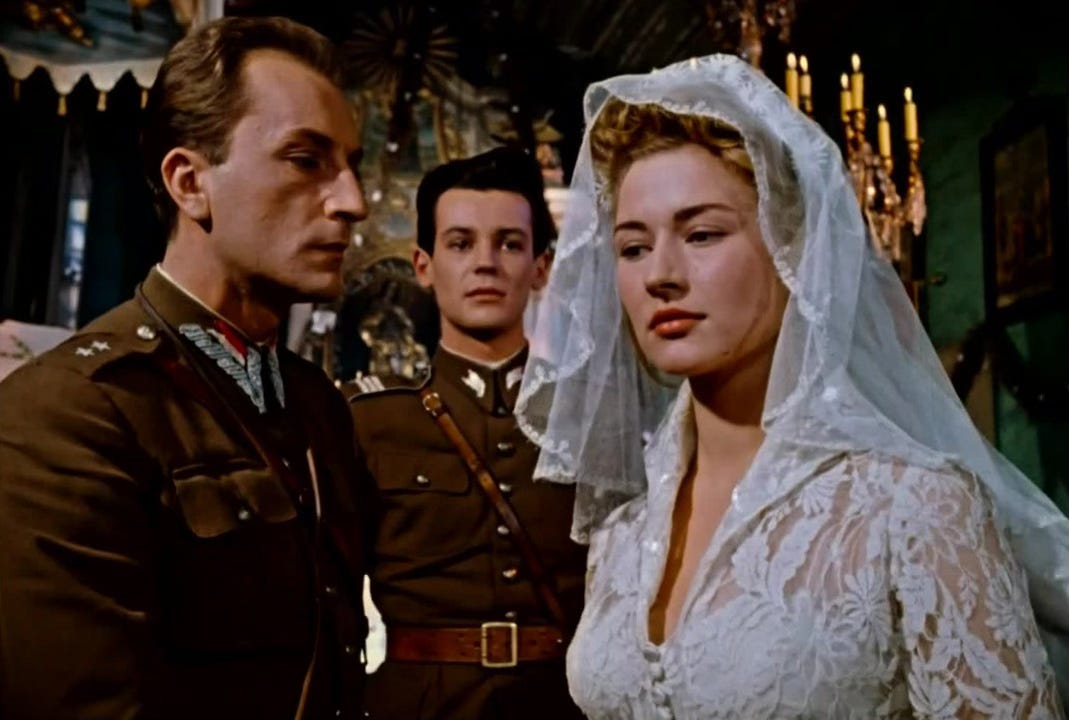

If I’ve barely mentioned the human characters thus far, that’s because there’s not much to say; with the focus being on the horse, they come across as more archetypes than rounded human beings. To complicate things further, the most charismatic figure, Pichelski’s officer, is killed off early, leaving Adam Pawlikowski and Jerzy Moes to pick up the narrative slack as his underlings. But neither of them were experienced enough to command the screen: Moes was making his feature debut, while Pawlikowski wasn’t a professional actor at all, and while he’d been surprisingly convincing in Ashes and Diamonds, that’s because he was acting opposite the mercurial Zbigniew Cybulski, and therefore didn’t have to do very much. Wajda said he briefly considered casting Cybulski in the part ultimately played by Moes, but opted not to because he knew that Cybulski would have been too dominant, and he was still fixated on the idea that the horse herself (now unavoidably miscast) was the film’s real protagonist. A love triangle with the schoolteacher Ewa (Bożena Kurowska) is charming enough, but similarly fails to strike many sparks; it’s not a patch on the doomed romances between Korab and Stokrotka in Kanal (or that same film’s Mądry and Halinka) or between Maciek and Krystyna in Ashes and Diamonds.

A failure, then, although Wajda never denied it—he’s been laceratingly, masochistically self-critical about it in interview after interview, and the experience undoubtedly taught him many valuable lessons. But it’s perhaps not surprising that, for his fifth feature Innocent Sorcerers (Niewinni czarodzieje, 1960), he’d finally abandon WWII for the present day and a wholly new subject that presented distinct challenges of its own.