Ashes and Diamonds

Popiół i diament, Poland, 1958, 97 mins, black and white

(This is one from the archives; my long out of print booklet essay for Arrow’s 2012 edition of Ashes and Diamonds, although I cut three now-redundant context-setting paragraphs on Socialist Realism, A Generation and Kanal, as I’ve tackled those on Substack in much more detail over the last couple of days.)

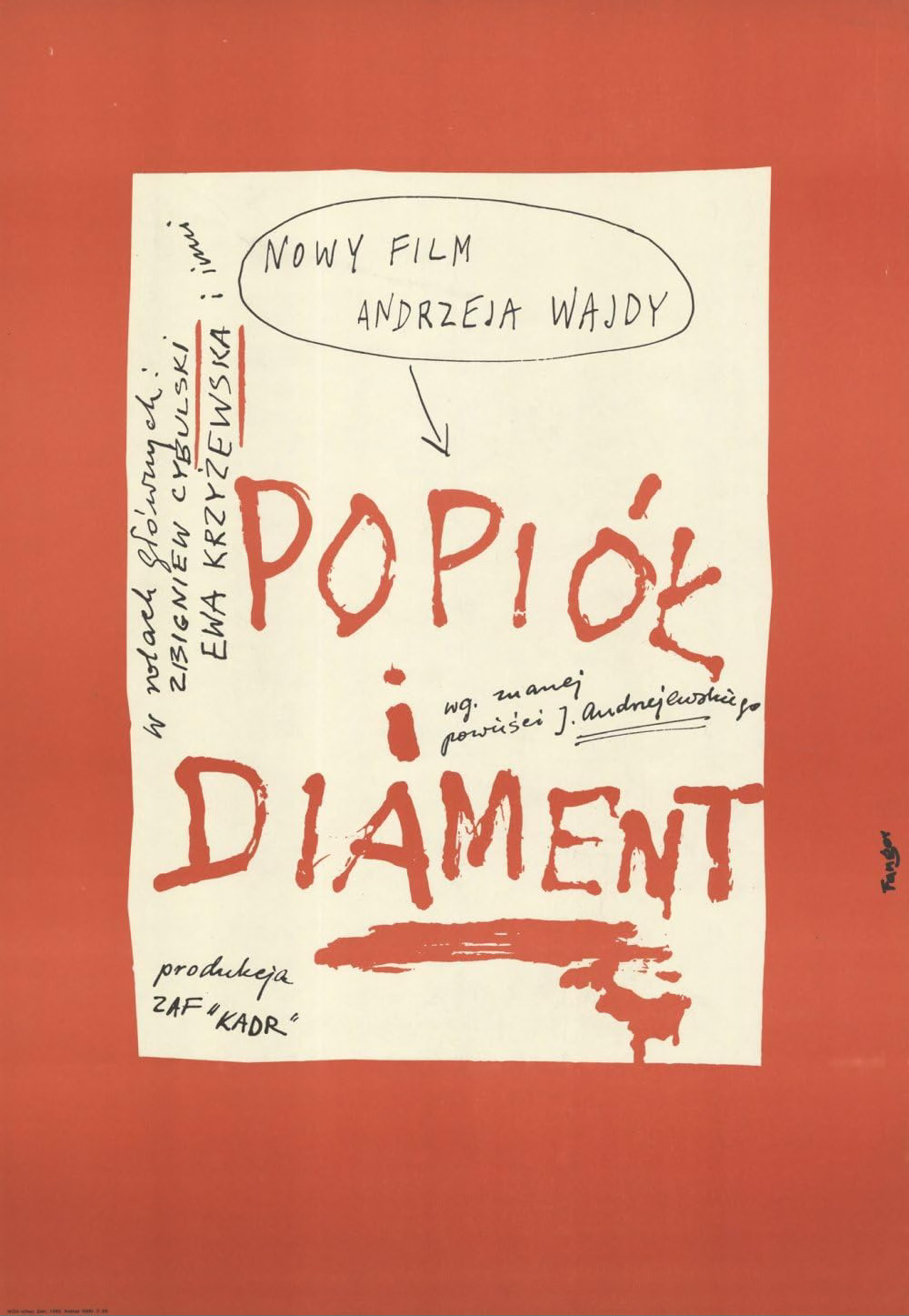

Director: Andrzej Wajda • Head of Production: Stanisław Adler, for Zespół Filmowy Kadr • Screenplay: Jerzy Andrzejewski, Andrzej Wajda, based on the novel by Jerzy Andrzejewski • Cinematography: Jerzy Wójcik • Editing: Halina Nawrocka • Production Designer: Roman Mann • Costumes: Katarzyna Chodorowicz • Sound: Bohdan Bieńkowski

Cast: Zbigniew Cybulski (Maciek Chełmicki), Ewa Krzyżewska (Krystyna), Wacław Zastrzeżyński (Szczuka), Adam Pawlikowski (Andrzej), Bogumił Kobiela (Drewnowski), Jan Ciecierski (Monopol hotel doorman), Stanisław Milski (editor Pieniążek), Artur Młodnicki (composer Kotowicz), Halina Kwiatkowska (Colonel Katarzyna Staniewiczowa), Ignacy Machowski (Major Florian), Zbigniew Skowroński (Słomka), Barbara Krafftówna (Stefka), Aleksander Sewruk (mayor Święcki), Zofia Czerwińska (barmaid Lili), Irena Orzecka (toilet attendant Jurgieluszka), Halina Siekierko (Puciatycka), Grażyna Staniszewska (singer Hanka Lewicka), Jerzy Adamczyk (Major Wrona), Adolf Chronicki (Podgórski), Wiktor Grotowicz (Franek Pawlicki), Mieczysław Łoza (Smolarski), Tadeusz Kalinowski (Wejchert), Ferdynand Matysik (Stanisław Gawlik)

It’s one of the iconic images of postwar European cinema: a man clad in leather jacket and dark glasses striking a pose with a machine gun. Like Alberto Korda’s 1960 image of Che Guevara, it helped define “rebel chic”, and it’s not hard to see why it helped cement Zbigniew Cybulski’s reputation as one of the great international film stars—an achievement all the more impressive for someone who did little outside his native Poland.

But when one watches the film containing this image, the impression is very different. Immediately after striking that pose, the assassin Maciek Chełmicki shoots two unarmed men dead, one in the back—and in front of a chapel under the sorrowing gaze of the crucified Christ, a symbolic notion whose significance could hardly be missed in what even after a decade of Communist rule was still a staunchly Catholic country. Although Maciek won’t himself discover this for a few more hours, the film reveals immediately that they weren’t even the intended victims, the actual targets turning up mere seconds after Maciek has hurriedly fled the scene, the dead men being innocent workers. This is hardly the act of a hero—but it beautifully encapsulates the ambiguity of Wajda’s film, its political and emotional complexity and its apparent refusal to take sides.

Jerzy Andrzejewski’s source novel was first published was published in 1948, and was rapidly hailed as a classic, with several film versions being proposed over the following decade: Wanda Jakubowska, Jerzy Zarzycki, Antoni Bohdziewicz and Jan Rybkowski were all connected with the property, and Bohdziewicz wrote three script drafts. Since these never-made films would almost certainly have been completed during the Socialist Realist period, it’s safe to assume that they’d have played very differently from what Andrzej Wajda eventually made.

Wajda first came across Ashes and Diamonds in the summer of 1957, when Tadeusz Janczar (who had already played Maciek Chełmicki in a 1956 radio adaptation of the novel) brought it to his attention. Coincidentally, Jan Rybkowski had decided not to film it himself, as he thought it was too similar to his own 1945-set WWII film The Hours of Hope (Godziny nadziej, 1955), and handed the project over to his younger colleague. Wajda’s first masterstroke was to ask Andrzejewski himself to co-write the screenplay, and indeed Andrzejewski’s is the name that we first see onscreen after the film’s title. This simultaneously provided an official authorial endorsement, while also granting Wajda the licence to make major changes to what by then had become an established school set text. Major narrative strands, notably the one about the wartime activities of various members of the Kossecki clan (only Andrzej Kossecki, Maciek’s superior officer, survived this cull) were jettisoned, and the action compressed from just under a week to less than 24 hours. Andrzejewski also collaborated on several significant structural changes, the most notable alteration being that of the protagonist: in the novel, it’s the Communist official Szczuka, in the film it’s the anti-Communist assassin Maciek.

In the context of Polish cinema at the time, this was a daring decision, and remained controversial right up to the point when the finished film was given its official ‘kolaudacja’ screening behind closed doors, during which the state’s Cinematography Committee would decide the extent of distribution, and also whether they required any alterations. One official (Wajda recalled that he only seemed to have a number, not a name) asked Wajda to remove the film’s final scene, but the director successfully persuaded the committee that the image of a man meeting his death on a rubbish tip (in the novel, he dies in the street) could be interpreted as “whoever raises his hand against People’s Poland will find himself on the rubbish tip of history”. The fact that it could also be interpreted as a scene in which callous Polish officials not only murder an unarmed man for no good reason (since they wouldn’t have been aware of the blood on his hands) but leave him to die in agony on a rubbish tip was, naturally, an unfortunate coincidence.

Knowing that censors are habitually more exercised by words than pictures, Wajda and Andrzejewski were canny enough to ensure that the screenplay, and the film’s dialogue, contained no overt political statements; any emphasis would be conveyed by the visual treatment and the casting. What one recalls from Ashes and Diamonds are not the debates about national identity and nostalgia for a ruined Warsaw but its overpowering images: the man whose bullet-riddled back bursts into flames, the effigy of the crucified Christ in the chapel (upside down and audibly creaking), the drunken Drewnowski spraying the fire extinguisher over the banquet guests, the unexpected appearance of a white horse (a longstanding symbol of Poland, and the central figure in Wajda’s next film Lotna), the fireworks suddenly illuminating Maciek and the dead Szczuka, the foppish master of ceremonies conducting a dance band’s ragged rendition of Chopin’s famous ‘Military’ Polonaise (op.40 no.1), above all the use of burning shot glasses to represent fallen comrades. This last metaphor was conceived by Wajda’s assistant Janusz Morgenstern, who went on to become a distinguished director himself.

Wajda initially trained as a painter, and although his early films were primarily influenced by the Italian neo-realists, even A Generation shows a tendency towards constructing self-consciously symbolic images, which when matched to a Wellesian fondness for wide angles and deep focus (cinematographer Jerzy Wójcik’s contribution is beyond praise) gives Ashes and Diamonds an Expressionist quality that some Western critics found strangely archaic in 1958. Some also found this mixture too overheated, though Wajda’s next film Lotna (1959) offers a more damning illustration of what happens when symbolism overwhelms the rest of the film.

Another crucial difference between Ashes and Diamonds and Lotna, masterpiece and misfire, derives from Wajda’s inspired choice of lead actor. Zbigniew Cybulski had already played a minor role in A Generation (in eerie anticipation of the events leading to Cybulski’s own accidental death in 1967, he’s shown running after a train), but was initially considered for the part of Maciek because he’d spent some time in Paris in 1957, where he’d discovered Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and the American method school. Although it’s overly simplistic to paint Cybulski as “the Polish James Dean” (not least because he died at 39, not 24, and made a far wider range of films), it was his prior familiarity with Dean’s work—then unscreened in Poland—that ensured that the director and star would understand each other perfectly.

Up to then, Wajda’s primary model when it came to directing actors had been the Italian neo-realists. Much of this is still true of Ashes and Diamonds, which is why Cybulski’s performance is so (deliberately) jarring, almost as though a very contemporary character from the late 1950s has been transplanted into an otherwise conventional WWII drama. Not only does this create a constant tension whenever Cybulski is onscreen, but it also singles him out as the film’s most intriguing character, ensuring that Maciek stands out even amongst a large and memorable cast. Throughout the film, Maciek seems to be rebelling not just against the historical inevitability of a Communist government, but against conventional notions of behaviour and propriety: he thinks nothing of marching into a chapel and using the altar as a convenient surface for repairing a shoe. The dark glasses helped fuel his iconic image, especially in the West—though he does at least have a historically plausible reason for wearing them: he explains to the barmaid Krystyna (Ewa Krzyżewska) that his eyesight was irreparably damaged going through the same experience in the Warsaw sewers that Wajda had depicted so vividly in Kanal.

Maciek isn’t so much a rebel without a cause as one whose cause has been comprehensively undermined by the Red Army’s expulsion of the Nazis from Poland (at one point, a tank drives past a huge portrait of Stalin). Being both anti-Nazi and anti-Communist, Maciek doesn’t fit the simplistically Manichean template drawn up by the same historical revisionists who pretended that the Katyń massacre (which killed Wajda’s own father Jakub) was a Nazi rather than Soviet crime. The film’s presentation of the complex politics of mid-1940s Poland is necessarily euphemistic (albeit far more detailed, nuanced and non-judgemental than would have been the case had the film been made not much earlier), but a great deal is conveyed in numerous conversations in which virtually all the film’s major and quite a few minor characters get a chance to reminisce about their wartime experiences and offer sufficient clues as to where they might have stood on the shifting sands of Polish patriotism.

Maciek is at least honest with himself about the futility of his present position, whereas the film’s other characters are either obsessed with the past (the romantic aristocrat Mrs Staniewicz, the journalist Pieniążek, the impresario Kotowicz, the Monopol porter) or creating an impossibly utopian future (Szczuka, Wrona, mayor-turned-minister Słomka). The third man in the opening attempt on Szczuka’s life, Drewnowski, is the most interesting case—played by the wonderfully weaselly Bogumił Kobiela (an actor who, like Cybulski, would die prematurely a decade later), he’s attempting to curry favour with both pro- and anti-Soviet factions in the hope of political preferment from whoever emerges on top. Meanwhile, while Szczuka himself (Wacław Zastrzeżyński) is no longer the narrative’s central player, he remains perhaps its most uncomplicatedly honourable figures, from his rousing impromptu speech to a gathering crowd of horrified workers to his genuine anxiety as to what’s become of his son, led astray by what he sees as subversive elements. And yet this is the man that Maciek has to kill: small wonder that he’s so conflicted, and why this internal struggle struck such a chord.